Controversial large-scale industrial development affects mangroves

Area of mangroves removed to build the anhydrous ammonia plant, next to Pemex and CFE facilities. (Photo: Google Earth).

OHUIRA

Construction of a large ammonia plant in the Santa María-Topolobampo-Ohuira wetlands and lagoon system, a Ramsar Site, in the municipality of Ahome, Sinaloa has been suspended due to irregularities in the permits and to resistance from the community.

In accordance with the Environmental Impact Statement summarized in the ecology journal Gaceta Ecològica published by the Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat), the company Gas y Petroquímica de Occidente intends to build an anhydrous ammonia (NH3) plant, with a daily production capacity of 2,200 tons. It also plans to install a network of 18-inch diameter pipelines that would carry natural gas and ammonia, and cover an area of about 98 acres.

Francisco Labastida Ochoa, project leader, has a long history in politics: He is a former presidential candidate in 2000 for the PRI party, ex-secretary of the Ministry of the Interior, ex-governor of Sinaloa, ex-president of the senate’s energy commission, and current director of the business and development consulting company Consultores en Desarrollo, Economía y Finanzas.

According to a report published in the daily newpaper Noroeste, Labastida Ochoa’s political influence can be felt in every aspect of the public sphere. He has received the endorsement of the current energy secretary, Pedro Joaquín Coldwell; the backing of his friends Mario López Valdez, the state’s governor, and businessman José Eduvigildo Carranza; as well as the support of businessman and politician, Rubén Félix Hays, and his own son, Francisco Labastida Gómez de la Torre, current Secretary of Economic Development and Strategic Projects of the state of Sinaloa.

The project was not initially approved by the National Commission on Natural Protected Areas (Conanp), a branch of Semarnat. Later, however, after a meeting with impresarios and politicians, Juan José Guerra Abud, the head of Semarnat at the time, fast-tracked project authorization.

The project’s international interests are represented by the Grupo Proman company, personally invited by Labastida Ochoa to form part of the industrial conglomerate. On its website this company touts itself as a leader in engineering and construction, with operations around the world in gas, petrochemical and steel processing, as well as infrastructure and the automobile industry.

The group declares itself to be an expert in key areas such as engineering, viability studies, construction, purchasing, marketing, and both project and services management. It is the largest producer of methanol in the world, with a presence on four contintents and in more than 12 countries. It has 31 operating subsidiaries and about 1,500 employees around the world.

In Mexico, the project entails the construction of a fertilizer factory with a daily production capacity of 2,200 tons, thereby turning the country into an exporter of the product, principally to Latin America, Asia and Europe.

The company states that it has an unwavering commitment to providing a safe, healthy, and gratifying workplace, as well as to protecting the environment, natural resources and local communities. It also states that its plants will use the latest proven technology available that minimize environmental impact. In addition, it says it is taking into consideration local environmental laws, and that the plants are designed to meet the most stringent international codes or local environmental laws and regulations.

This is the political and economic power with which local fishermen, residents, and environmental activists are faced. They hope the permits will be withdrawn that allow construction of one of the largest fertilizer plants in Latin America, and lead to the destruction of this natural wetland. They see investors as trying to take advantage of the natural gas supply and the proximity of the deep-sea port in Toplobampo, which translates into cheap energy and quick access to the foreign market.

Detractors point to corruption and influence peddling, the total absence of ethics and social responsibility, as well as a lack of respect for international agreements, treaties, and conventions signed by Mexico, which are allowing the multi-million dollar investment to take place within the ninth most important wetland in Mexico, also a protected Ramsar site.

At the moment there are at least two complaints against the construction of the fertilizer plant, the first made by ex-federal delegate Gerardo Peña Avilés who is representing 3,000 fisherman from 13 cooperatives. He made a formal environmental complaint against the project for “having carried out activities, acts and omissions that have caused grave damage to the area’s ecosystems, for example to the habitat of protected species of wild flora and fauna, as well as direct damages to the wetland vegetation and to the mangrove forest ecosystem.”

The Federal Attorney of Environmental Protection (Profepa) received the complaint in Mexico City on Aug. 27, 2015. It was accompanied by a technical report detailing the violation of a number of federal laws and asking that the agency verify these violations and impose a number of security measures.

The complaint asked for the temporary, partial or total closure and cessation of work on any installations, machinery or equipment, and sources of contaminants, as applicable, that are being used in a manner that can be harmful to the area’s biodiversity or natural resources.

According to Peña Avilés, the demand was partially addressed when the infilling of the wetlands was halted and only minor works are now being carried out. Another of the demands is a neutralization process or any other similar action that prevents materials or dangerous residues from creating an ecological imbalance or from harming or causing severe deterioration of the natural resources.

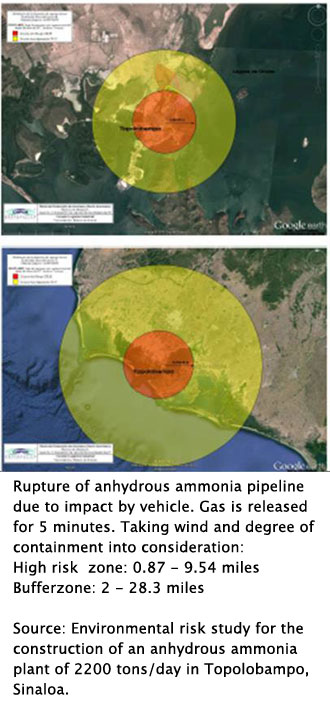

The ammonia plant is located next to a number of other industrial plants, a Pemex petroleum storage facility, and a thermal power station run by the federal electric commission (CFE), all of which present, in the eyes of academic and environmentalist Sandra Guido, an impending threat to the environment.

Guido writes on her Facebook page: “Beyond the potential environmental damage to this internationally recognized Ramsar Wetlands Site, the risks to the residents must be evaluated in terms of the chances of an accident occurring at the plant, or even worse, of a combined conflagration involving the ammonia plant, the energy plant, and the petroleum stores.”

According to the Culiacán newspaper Río Doce, the Topolobampo housing committee [El Comité Único de la Vivienda] also expressed its disgust with the industrial project, calling on the fishing community’s residents to engage in a massive mobilization repudiating the new investments. Gorgonio Silva Gualizapa accused the government and the business people of not caring about the grave ecological risks and the health of the residents of the Ahome fishing cooperatives, and asked that the destruction of the estuary be stopped.

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, known as the Ramsar Convention, was signed in the Iranian City of the same name in 1971. Its mission is “the conservation and wise use of all wetlands through local and national actions and international cooperation, as a contribution towards achieving sustainable development throughout the world.” (Ramsar, 1971)

Ramsar has 169 members. Mexico joined in 1986 and has 142 sites designated as Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Sites), with an area of 2.14 million acres.

According to Ramsar’s technical data sheet, the Santa María-Topolobampo-Ohuira lagoons, site of the planned industrial plant, are of great environmental importance: The three coastal lagoons are designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and Biosphere Reserve. They are part of the Gulf of California Islands Protected Area for Flora and Fauna, which also has a total of eight islands, six of them within Bahía de Ohuira.

All of the mangrove species found in Mexico are present in the lagoon complex. It is home to 84 percent of the aquatic migratory birds found wintering in Mexico. It is subjected to inundations and storms from tropical cyclones that are produced regularly in the region, and the lagoons function as a coastal stabilizer by reducing the energy and speed of runoff produced by rain.

Ramsar found that the Reddish Egret (Egretta rufescens), a species subject to special protection under Mexican law (NOM-ECOL-059-2001), nests within the island complex, which is also a feeding and breeding ground for protected Olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), Green (Chelonia agassizii), Leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) and Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) sea turtles from adolescence through adult stages. All of these species are described as endangered on the IUCN Red List, with the last two species designated as critically endangered.

The four species of mangroves present are subject to special protection, mainly because they harbor the reproductive phase of a number of commercially important marine species including shrimp, oyster, and a variety of fish. A number of cacti, such as tasajo (Peniocereus marianus) and viznaguita (Echinocereus sciurus var floresii), which is endemic to the Topolobampo area and has only been reported from Isla Mazocahui, are also protected, as a number of other plants.

The Santa María-Topolobampo-Ohuira Lagoons comprise the ninth highest priority site of Mexico’s 28 top priority wetlands, as identified by Ducks Unlimited de México (DUMAC), because they harbor 84 percent of all the aquatic migratory birds found to winter throughout Mexico. Found seasonally in the wetlands are: 65 percent of the Common Teals (Anas crecca); 69 percent of the Northern Pintails (Anas acuta); 84 percent of the Blue-winged Teals (Anas discors); 68 percent of the Northern Shovelers (Anas clypeata); 76 percent of the Gadwalls (Anas strepera); 77 percent of the American Widgeons (Anas americana); 92 percent of the Black-bellied Whistling-ducks and Fulvous Whistling-ducks (Dendrocygna autumnalis and D. bicolor); 91 percent of the Redheads (Aythya americana); and 63 percent of the Lesser Scaups (Aythya affinis).

On Isla de Patos, more than 20,000 birds of a number of pelican species have been counted, while the area’s population of Common Teal (Anas crecca) sits around 3 million birds and that of the Northern Shoveler (Anas clypeata) at 4.641 million.

Following are some of the species of birds that reside in the lagoon system and their level of protection, according to the Mexican law NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (Environmental Protection-Native Mexican Species of Wild Flora and Fauna) and in accordance with the technical report presented by Peña Avilés:

- California Brown Pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis)—Threatened.

- Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias)—Protected endemic.

- Bluefooted Booby (Sula nebouxii)—Subject to Special Protection.

- Heermann’s Gull (Larus heermanni)—Subject to Special Protection.

- American Oystercatcher(Haematopus palliatus)— Endangered

- Bottlenosed Dolphin (Tursiops truncatus)—Subject to Special Protection.

- Mexican Spiny-tailed Iguana (Ctenosaura pectinata)—Subject to Special Protection.

- Black Mangrove (Avicennia germinans)—Threatened.

- Red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle)—Threatened.

The complaint’s supporting document refutes each of the points endorsed by Semarnat and used to rush through the approval of the project. The most outstanding of these are:

“… no removal, landfill, transplantation, pruning or any other type of work or activity that affects the integrity of the hydrologic flow of the mangrove will be carried out …”

“… the implementation of the project would not have any direct interaction with Isla de los Patos or with the species present on it …”

“… the project meets this specification given that no work will be carried out in the mangroves and it will also not affect the flow towards nearby mangroves, such as those found to the north of the company’s property …”

“… the project will not be carried out on forest land or areas suitable for forests. At the same time, the construction of the current project will not affect any mangrove trees …”

“… If the project does not remove mangrove then it can be authorized …”

The technical report concludes that the removal and elimination of mangroves by the said project has occurred, so the governmental agencies can object and even stop the work done on site up until now due to noncompliance with Semarnat rule.